Giana pushed her weight against the weak door. The lock had rusted several months back, but none of the blacksmiths in town were working. So the door gave way without much effort.

Poor Papa lay in bed. He was sweaty, and there was a large purplish lump on his neck about the size of a chicken egg. Giana didn’t understand. She had seen him only hours ago and he’d been fine. Now he looked like he was on Death’s Door. In days, if not hours, he could become one of the bodies she’d witnessed daily taken away by the cart. Giana started to cry.

“Don’t cry for me, daughter. Leave while you can.” Papa could barely croke out the words.

“No. I won’t leave you!” Giana would cure her father. She was determined. She ran to the backyard and grabbed a chicken. She had heard that if you plucked a chicken and rubbed it over the affected parts of the body, you could draw the sickness out. Once she returned to the room she told her Papa, “Hold still!” while she applied the plucked chicken to the site of the purple lump. Papa tried to struggle, but he was too weak to do anything. After Giana was done, Papa closed his eyes.

“It's okay, you can sleep now, Papa.” Giana held her hand to her father’s forehead. He was burning up. Giana knew Papa would not recover in time to catch Lady Francesca’s carriage, so she decided to rest on the floor next to Papa, a bouquet of fragrant flowers pressed against her nose, for protection.. When she awoke, she felt something sore growing underneath her armpit.

It might come as a surprise to modern audiences, but some of the same measures that were used to combat the spread of COVID-19 in the 21st century were also used for the first time in medieval Europe. As the Black Death ripped through the continent, societies desperately sought out new ways to combat the spread of the illness. One approach became known as quarantine. This began in Venice in the 14th century, but it was common in other maritime cities.

In effect, this approach required ships arriving in the city’s port to sit at anchor – away from the city – for 40 days before landing and allowing the passengers and crew to enter the city. This is where the term ‘quarantine’ comes from, deriving from the Italian qaranta, meaning ‘forty’.

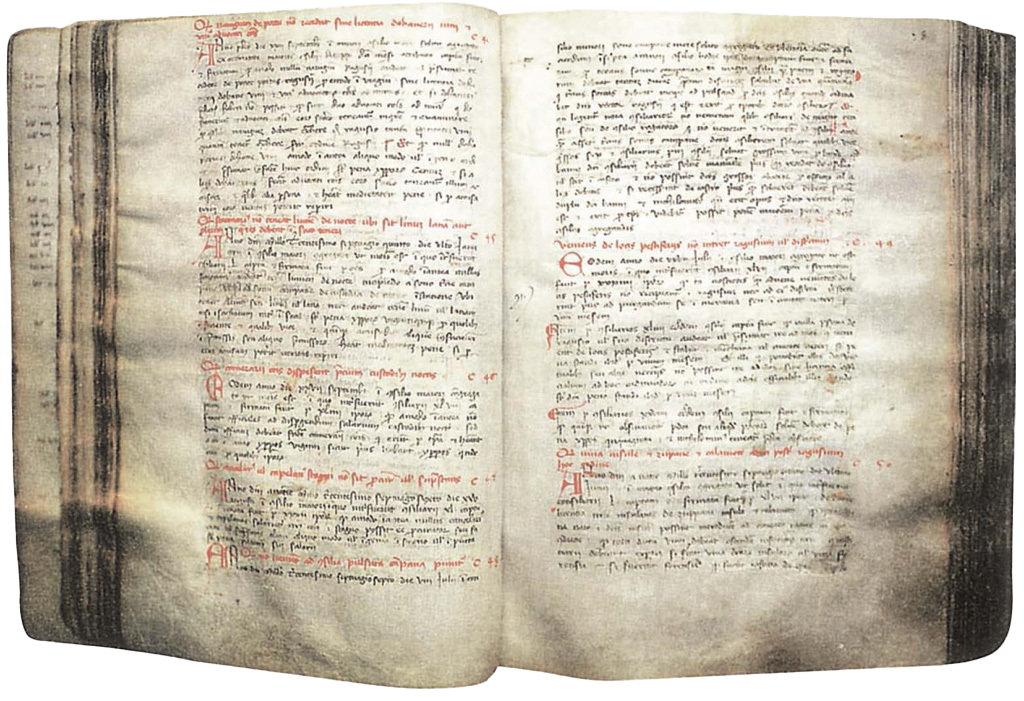

Quarantine was also used by the city of Dubrovnik, on the Adriatic coast of Croatia, south of Venice. Historians have uncovered records of meetings of the town council that took place in 1377 as the plague threatened to return to the city. The council introduced a law that stipulated that ships were not allowed to disembark at Dubrovnik, unless they had previously spent a month on the island of Mrkan, or the town of Cavtat (quite what the residents of Cavtat thought of this measure remains to be seen!).

Isolating victims of certain diseases had been used before in medieval medicine. Because the disease could be so disfiguring, people suffering from leprosy were also driven out of their communities by others who were afraid of catching the disease.

One of the most important of the rational ideas about the spread of disease in the Middle Ages was the theory of miasma. The term derives from the ancient Greek word for “pollution”. Miasma theory was the idea that diseases were spread by a “bad air”, which could be caused by rotting organic matter (i.e. if something smelt bad, there was a good chance that it was bad for your health). This could include things such as rotting food, but also dead bodies. This was important during the Black Death, because corpses were a common sight in communities as the spread of the disease overwhelmed the capacity to dispose of bodies. It’s not hard to imagine why people connected the smell of the rotting corpses and the continued spread of the disease.

In general, towns and cities in medieval Europe would have been pretty stinky and public health was generally bad. People often threw their waste into the streets and into nearby rivers; unfortunately, this would also often have been the same source from where the local community would have drawn their water. Issues were made worse when, if there was heavy rain, the cesspits would overflow.

The belief in the theory of miasma did encourage some attempts at sanitation in medieval Europe. For example, swamps and marshes in urban centres were drained, and waste piles were moved away from places where people lived.

The theory of Miasma remained popular well into the 19th century, despite being ultimately incorrect. Another benefit of the belief was that it did encourage some measures to improve public health, as well as suggesting a link between dirtiness and disease (even if the germs that were the true cause remained a mystery).

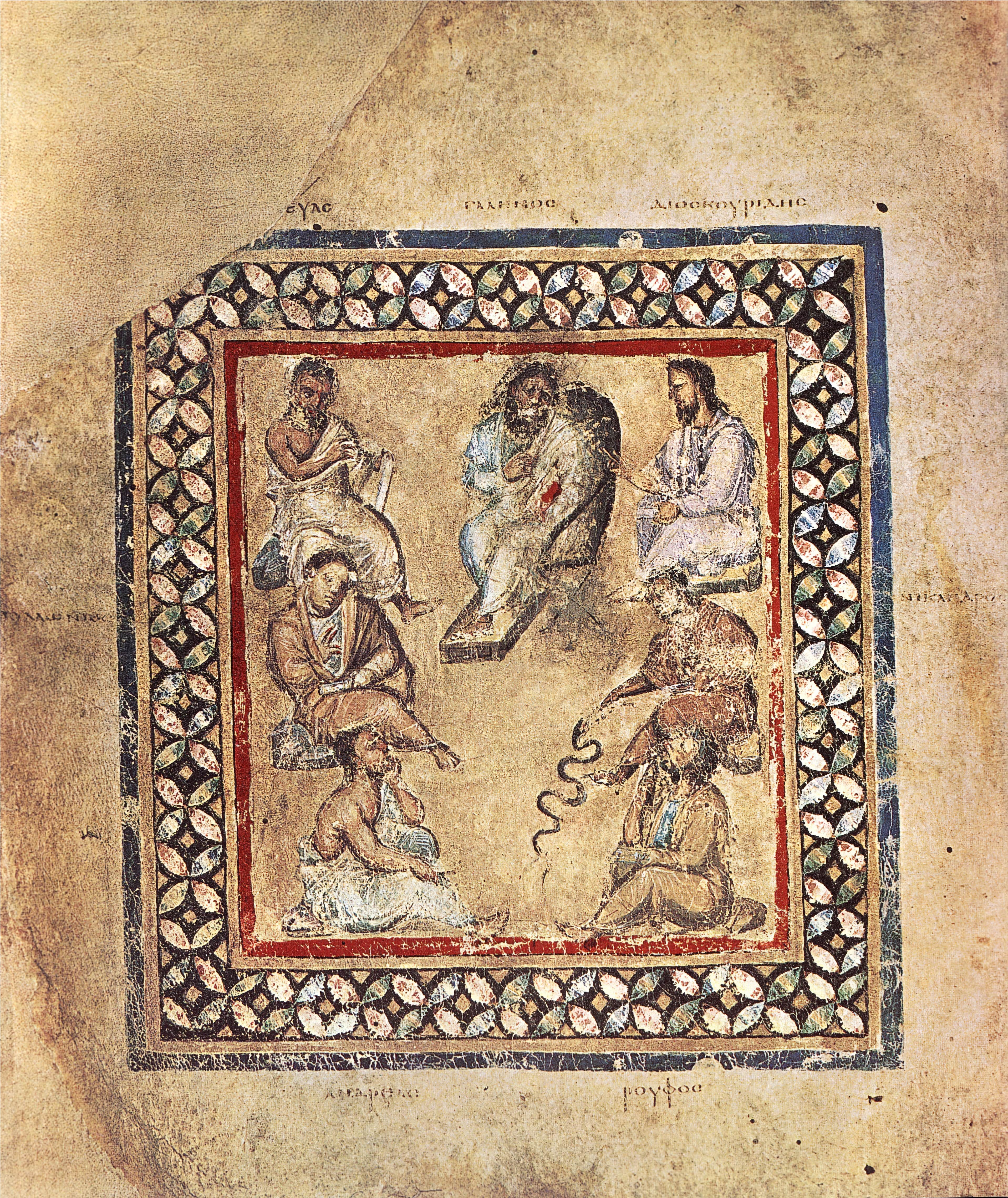

In 14th century Europe, many societies across the continent were beginning to reconnect with the ‘Classics’, which refers to ideas and practices that were first used by the societies of ancient Greece and Rome. Over the course of the 15th century, this would become known as the Renaissance (literally, the ‘rebirth’). During this earlier period, however, some medical ideas from the ancient world were also important. Perhaps the most important ancient medical thinker was Galen.

Galen was a Roman physician from the city of Pergamon (in modern Turkey). He had lived during the late second century AD and had worked as the doctor for the emperor Marcus Aurelius (and his son, Commodus). Galen wrote extensively on medicine and surgery, and many of his theories built on the foundations set out by Hippocrates, the ancient Greek doctor from the 5th century BC. Importantly, Galen supported the ideas of observation and encouraged doctors to examine a patient’s symptoms to diagnose their illnesses. Miasma theory also featured in Galen’s teachings about medicine and illness.

During his life, he had practiced dissection on animals (especially pigs and apes), and these informed his ideas. However, because the Church banned dissection, several of Galen’s mistakes went unnoticed for centuries.

Galen’s main contribution to an understanding of medicine was to offer a development of Hippocrates’ theory of the Four Humours. This theory had stated that for a person to be healthy, they had to maintain balance between their humours: Choler (Yellow bile), Blood, Phlegm, and Black bile. A patient became sick when there was an excess of one of these humours.

“At all events, bloodletting should be carried out when the plague first strikes…” Extract from a letter sent by a group of doctors in Oxford to the Lord Mayor of London, ca. 1350.

Galen established a theory of opposites that used the Four Humours as a foundation. He taught that an illness could be cured by using treatments that opposed a patient’s symptoms. For example, if a patient had a fever – which was hot – this was caused by an excess of blood. To combat this, a patient could be bled, perhaps by using leeches or visiting a barber surgeon.

Medicine in the Middle Ages was characterised by a curious combination of superstitious beliefs and attempts to use rationality to identify the causes of and treatments for various maladies. The same tension between the superstitious and rational is evident in medieval doctors.

Medicine in medieval Europe was regulated and all doctors were expected to be sufficiently trained. As early as 1140, Roger of Sicily had forbidden anyone from practicing medicine without a license. Universities had begun to open around the continent, and during the 12th century, many of these had medical schools. Doctors studied the works of figures from antiquity, such as Hippocrates and Galen. Many of these works had been preserved and translated by scholars and doctors from the Arabic Empires in the east, such as Avicenna (also known as Ibn Sina).

The most famous early medical school was at Salerno, in southern Italy, but there were numerous other examples. The Medical school at Montpellier, which would be where Guy de Chauliac trained, was famous for its research into anatomy. Because of their training, doctors were comparatively uncommon.

Medieval doctors applied a number of approaches in treating diseases. This included diagnosis, where they studied their patient’s symptoms. Doctors would check pulses, observe the patient, and – sometimes – even taste the patient’s urine! This is known as urology, and as well as the taste, doctors would examine the colour and smell of urine to ty to work out which humour was imbalanced.

Often their diagnoses would be informed by Galen’s Theory of the Opposites and a belief in the Four Humours, and sometimes also by astrology, which meant that doctors would use the alignment of the stars to inform their diagnoses. Surgery was possible in the Middle Ages, but it was basic, very dangerous, and incredibly painful: there was no knowledge of antiseptic practices to keep things hygienic, and there were no anaesthetics to fight the pain for a patient. Operations ranging from tooth extractions to amputation were still practiced, but they were high risk to the patient.

Not every community had a doctor, and where they did work, they were often expensive, so people had to find alternatives. They could go to the local barber surgeon. These were not university-trained medical practitioners, but they would provide some “services”, including blood letting to balance the humours.

Generally, government in the Middle Ages operated on a local level – that is to say affecting a city and its immediate environs – rather than the national. Because of this, although politics could work to improve public health, responses to emergencies often varied. The lack of concentrated efforts meant that diseases such as the Black Death were able to spread more easily.

Some attempts were made to stop the spread of the disease, and valuable evidence is preserved from the “Ordinances for sanitation in a time of mortality” issued by the Tuscan town of Pistoia in Italy. Following the arrival of the plague in early 1348, the town magistrates enforced a number of rule changes to try to limit the spread. This included limiting hte entrance of exit of people and material from the town, as well as instructions that were clearly informed by a belief in miasma theory:

“In order to avoid the foul stench which the bodies of the dead give off they have provided and ordered that any ditch in which a dead body is to be buried must be dug underground to a depth of 2 1/2 braccia by the measure of the city of Pistoia.” Ordinances for sanitation in a time of mortality, 1348

There are examples of this in medieval England, where individual cities took steps in the aftermath of the Black Death to improve public health. Several of these responses can be directly connected to a belief in miasma theory. For example, in the early fifteenth century (1421), the Mayor of Coventry ordered that everyone was responsible for cleaning the front of their house every Saturday; if they failed to do so, they were liable to pay a fine. There were also designated dunghills for people to dispose of their waste, and people were banned from dumping their waste in the river Sherbourne, which flows through the city. Prior to this, the Mayor of London had banned the slaughter of large animals inside the city walls to prevent pollution in 1371. There is some evidence of plans with a wider focus, but these are less common. For instance, in 1388 the English Parliament passed a law fining people £20 (a huge sum in medieval England) for throwing waste into ponds and rivers.