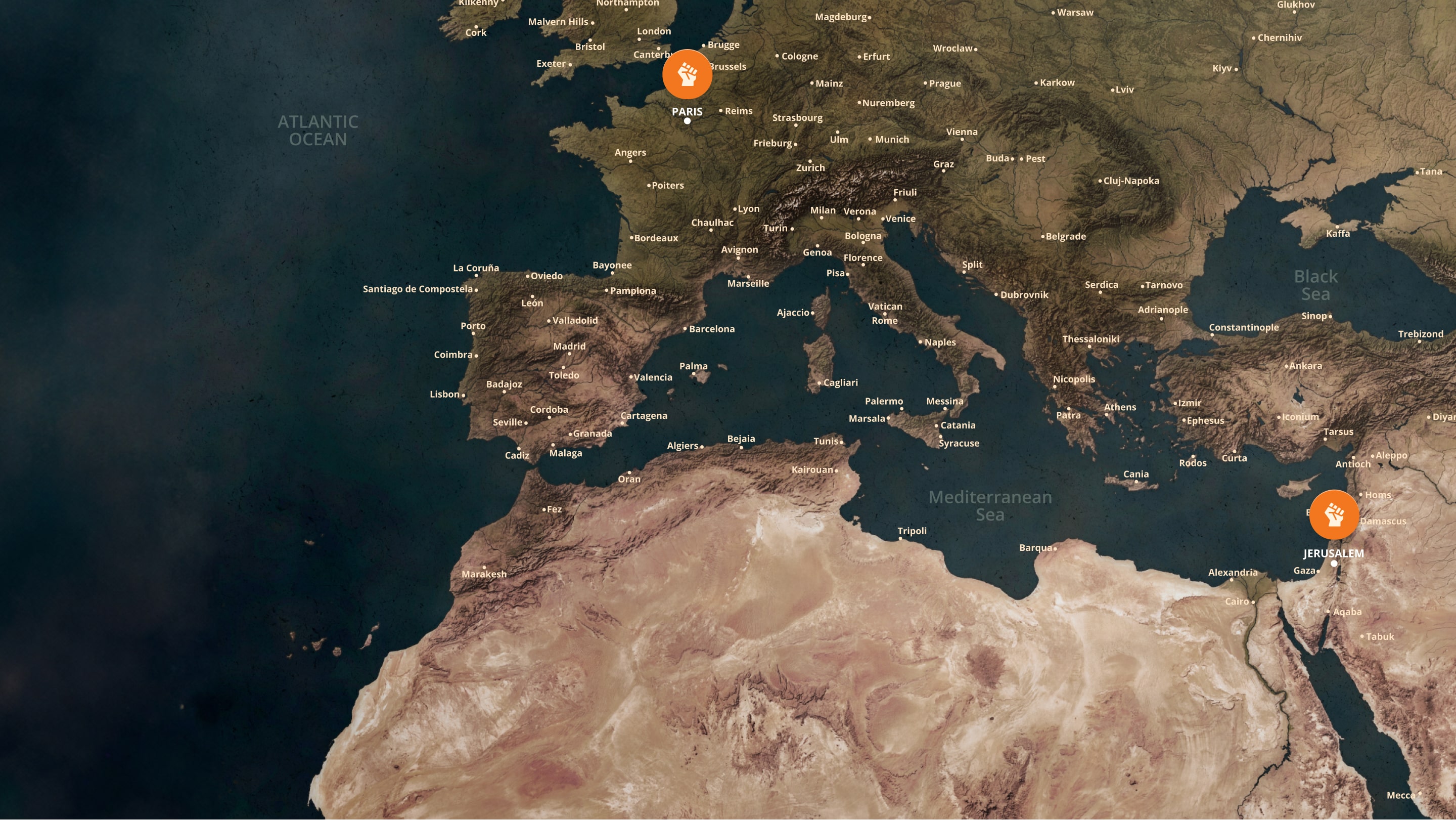

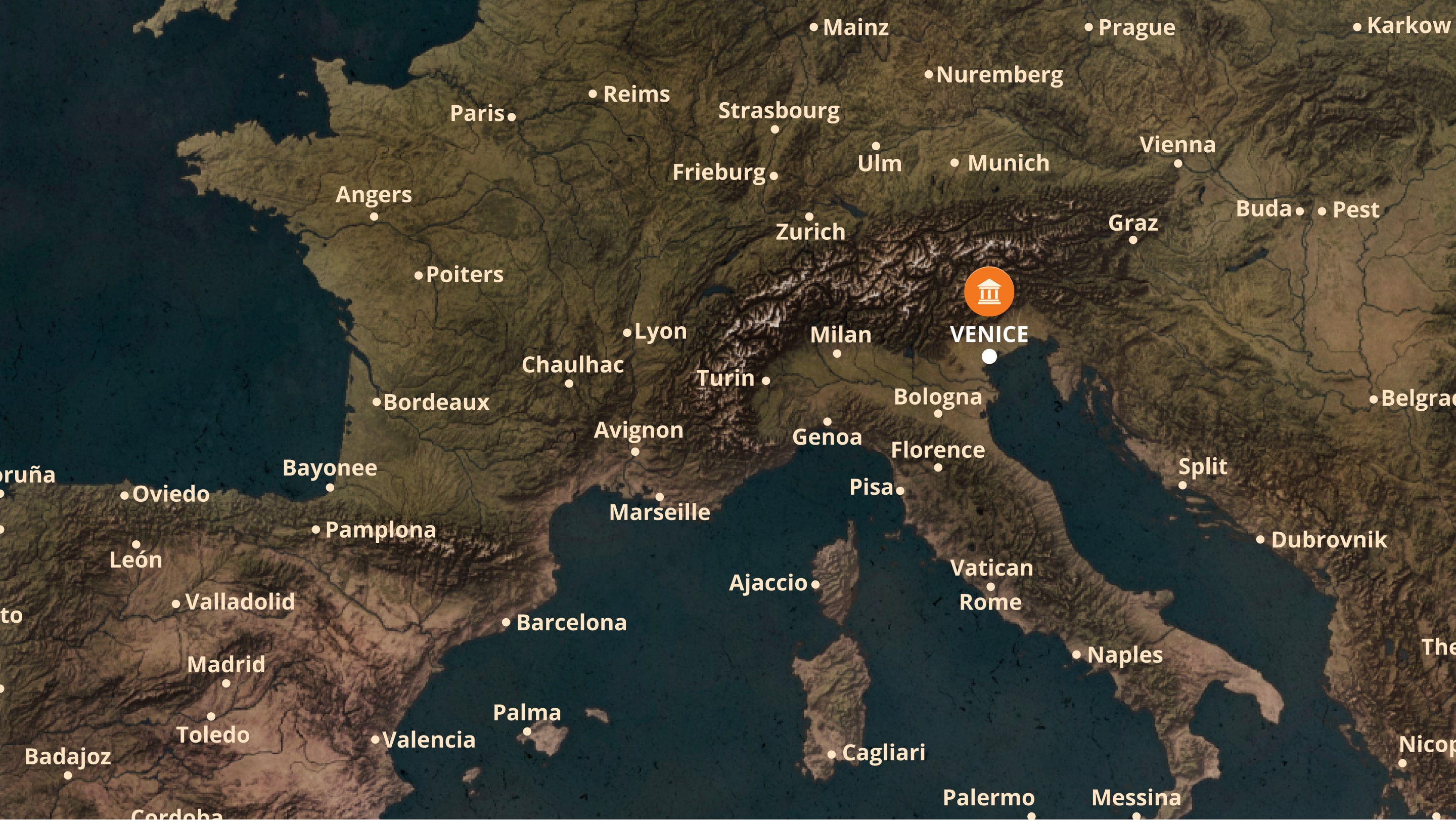

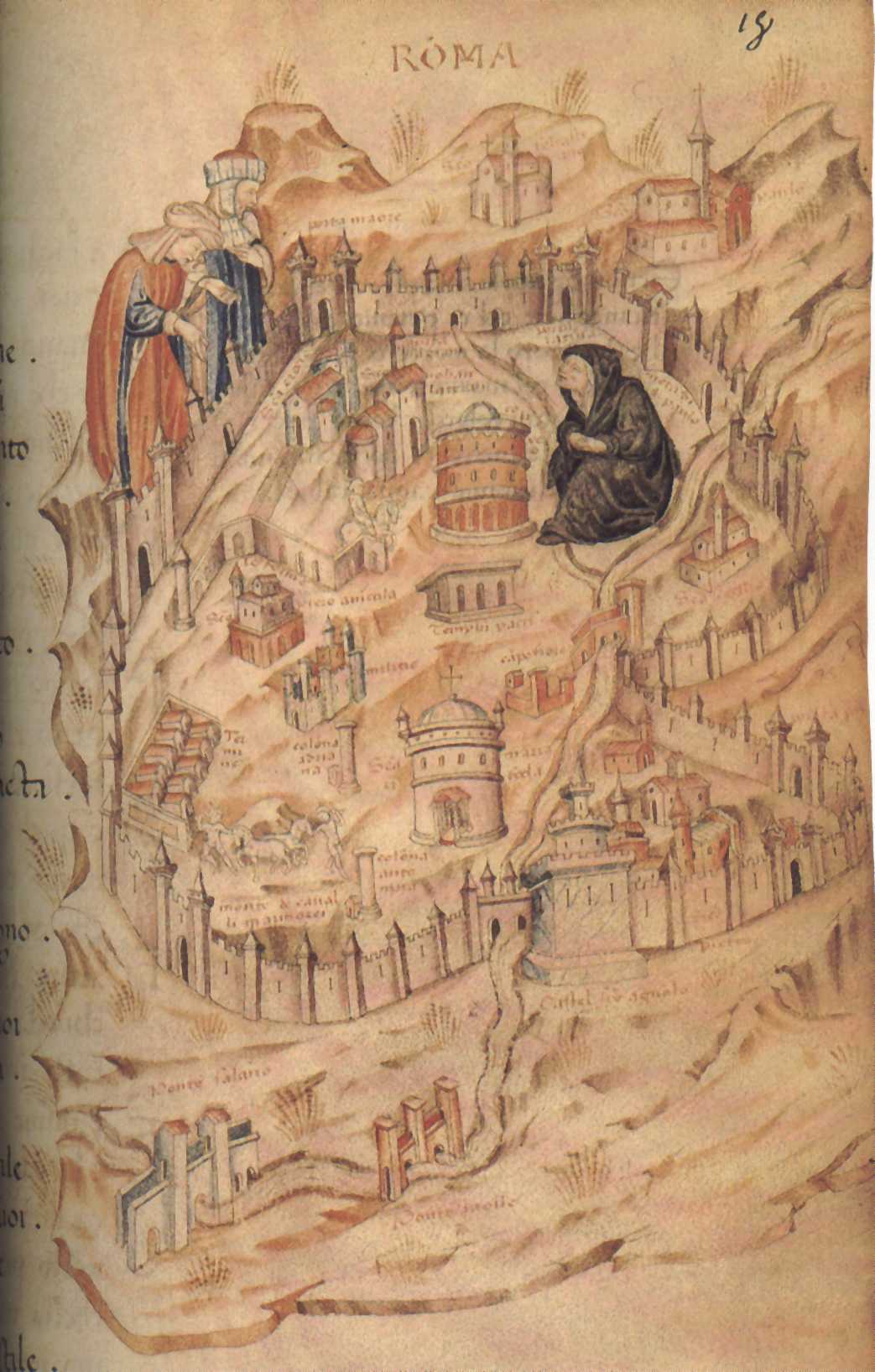

By the 14th century, Venice was the dominant power in the eastern Mediterranean. The republic’s influence was aided by its geography, which in turn offered a wealth of economic advantages. In short, with its strong navy, Venice was well situated to operate as the gateway for trade between the east and west. They had been involved in this process for some time already, and the republic enjoyed the advantages of free trade in the Holy Land, a reward for having previously helped the crusaders.

The Great Council organised regular convoys (known as mudae) of merchant galleys to sail from the Venetian lagblaoon across Europe, Asia, and North Africa, bringing goods back and forth between Constantinople, London, Brugge, and Tunis. Because the city owed so much of its power and wealth to the sea, the Venetians established the annual ceremony of the Sposalizio del Mare (‘The Marriage of the Sea’). The ceremony celebrated the republic’s relationship with the sea. From 1177, the Doge would lead a procession of boats out to sea, whereupon the city’s chief magistrate would take a ring from his finger and throw it into the ocean, symbolising the city’s marriage to the sea!

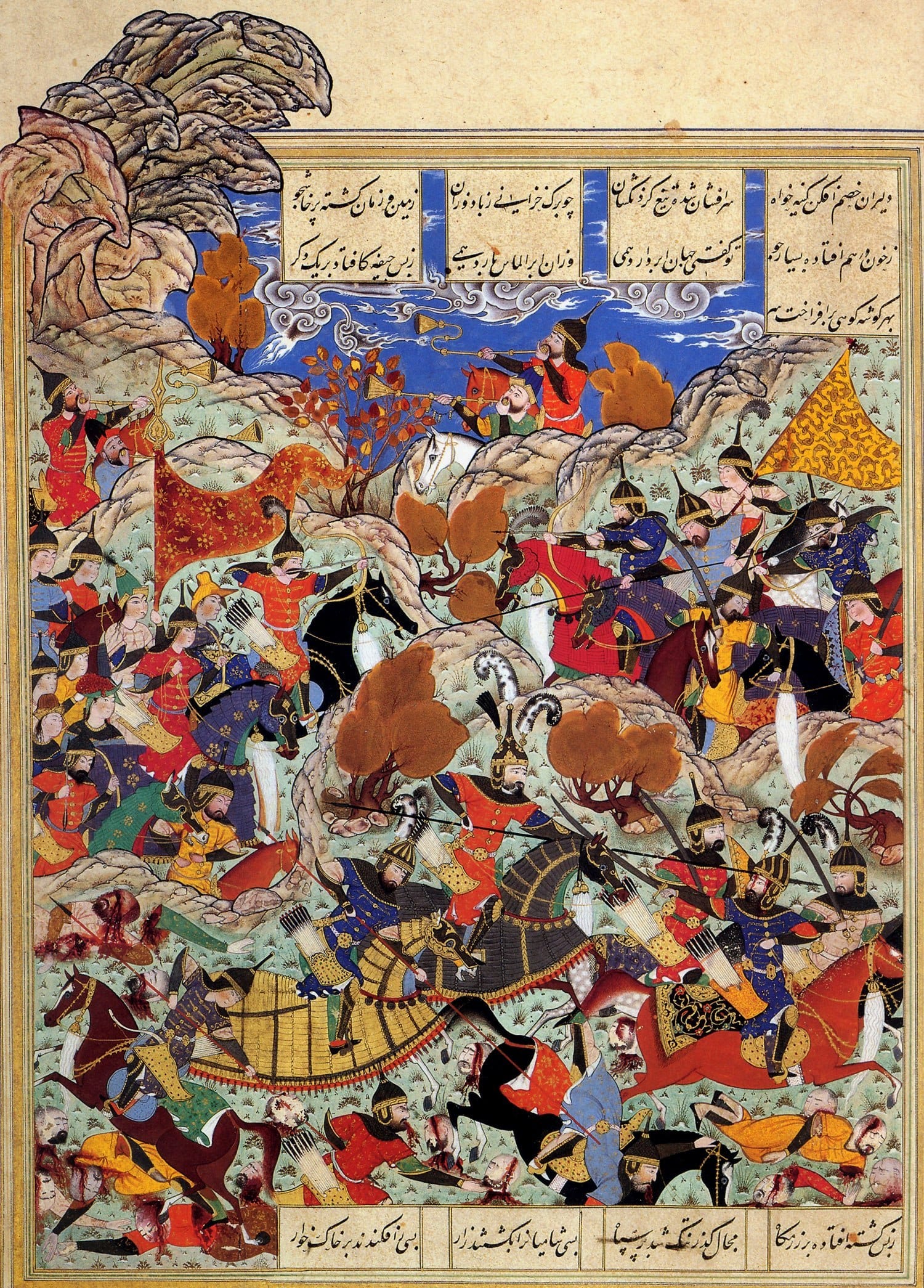

Alongside the city’s maritime trade, it was enriched spectacularly by the silk roads. These were the trade routes, overland, that connected Asia with Europe. The Venetians had agreed a trade treaty with the Mongol Empire as early as 1221, a sure sign of their ambitions. Asia was prized as a source of expensive luxuries that could be sold for high prices in European markets.

Venice’s relationship with the markets and empires of the east gave rise to one of the most famous stories in history, that of Marco Polo, and his journeys across Asia. The Venetian traveller left the city in 1271. He returned in 1295, rich with stories of the cultures, traditions, and people of the east that he had encountered on his travels. The stories spread across Europe and did much to fuel a fascination with exploration and the opportunities for economic exploitation this offered.

Of course, as the Venetians would find out in the terrible events of the 14th century, ideas and riches weren’t the only things that could travel across these trade routes…

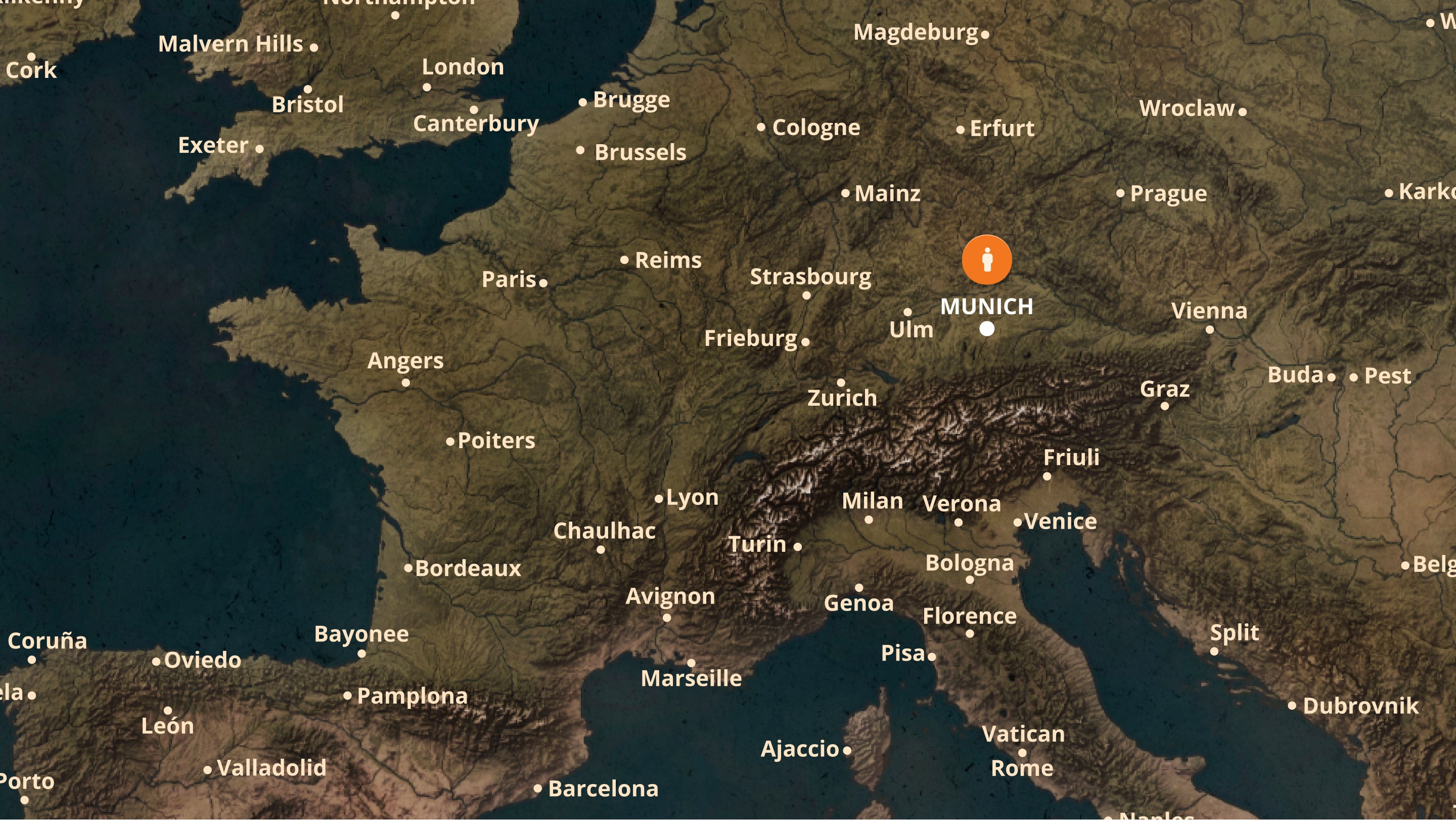

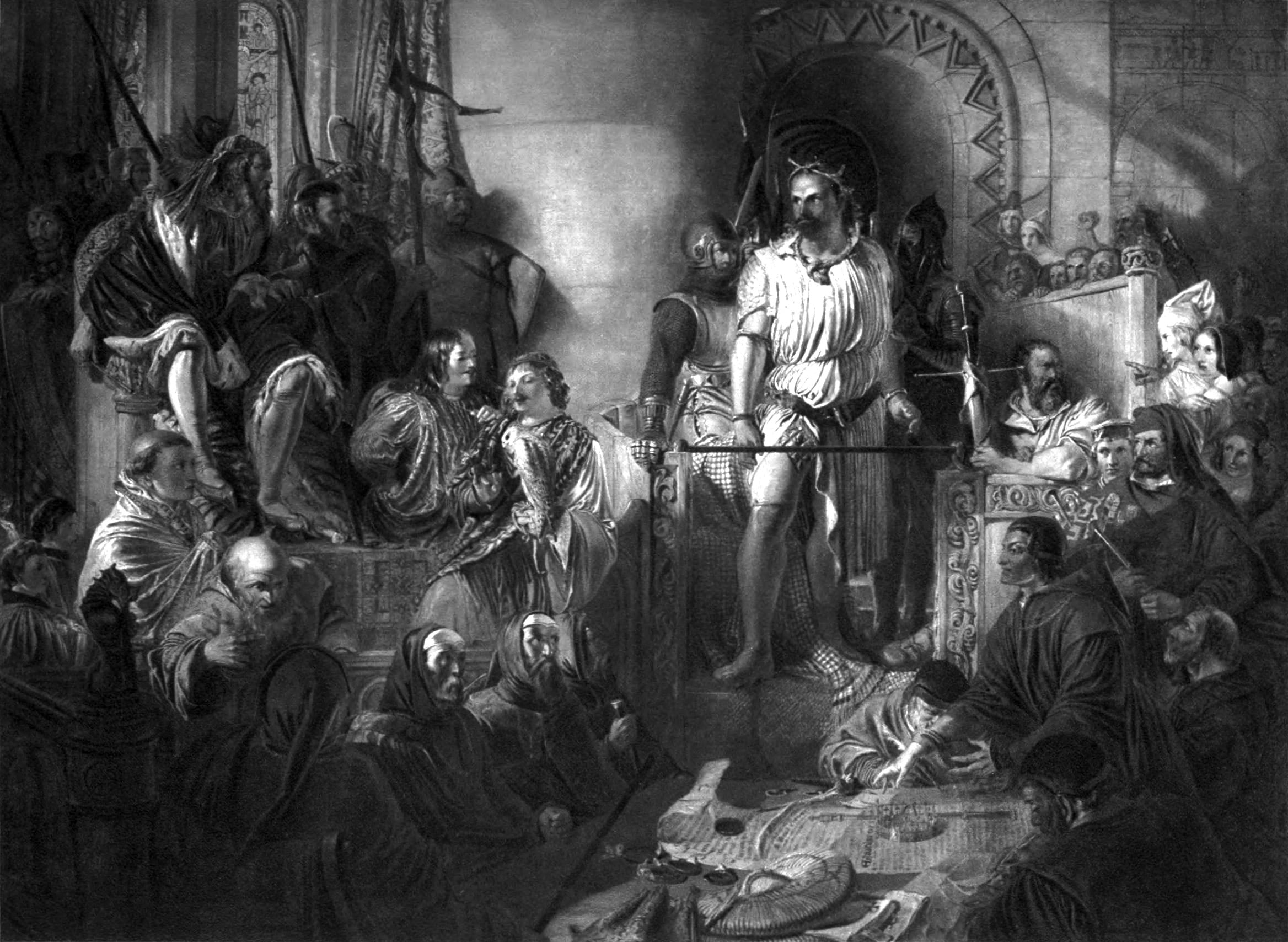

According to legend, the Swiss marksman, William Tell, assassinated the Albrecht Gessler, a tyrannical reeve. The tale symbolises the Swiss struggle against the Habsburg ruling dynasty and feudalism.

The Flagellants, a group of penitent religious zealots, first appear in Germany. They march through towns, hooded and half-naked, lashing themselves with whips as a sign of their devotion to God and an attempt to appease the divine retribution that the plague was believed to be.

2,000 Jewish people are burned alive in the town of Strasbourg. Later that year, some 3,000 Jews attempt to defend themselves from persecution in the German town of Mainz, before being overpowered by the Christian residents and killed.

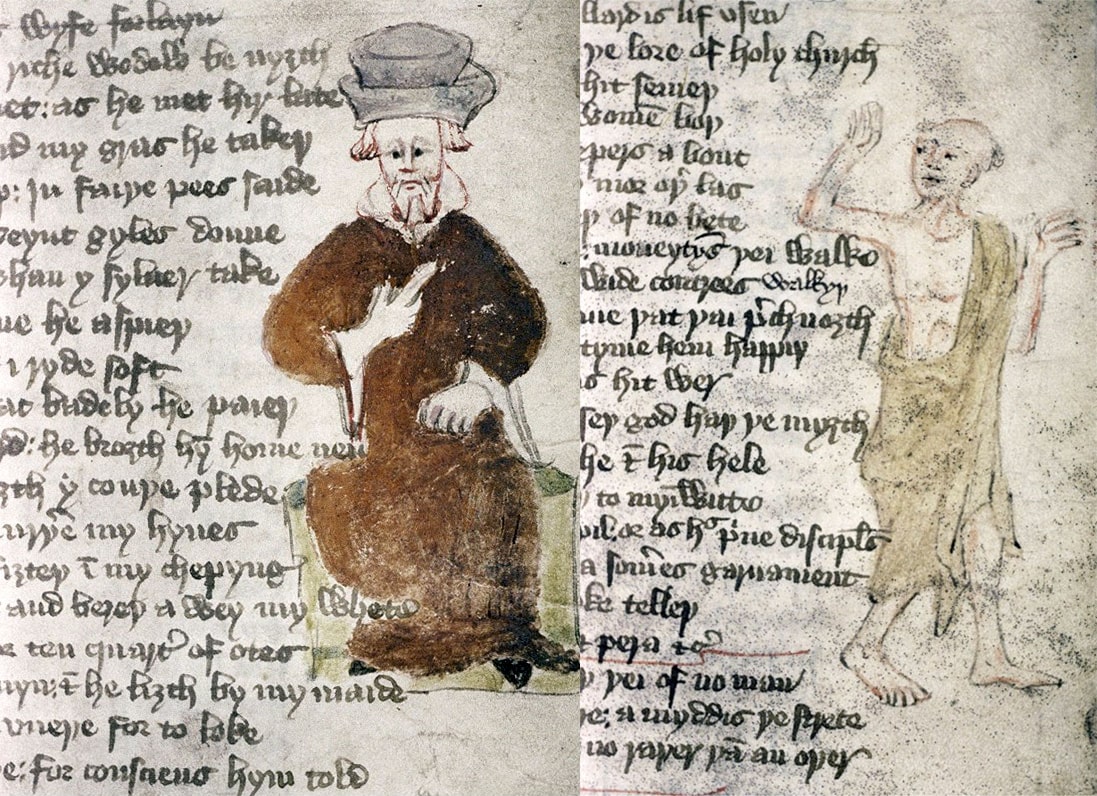

William Langland writes the allegorical poem Piers Plowman. It contains the first reference to a literary tradition of Robin Hood tales. The poem combines theological allegory and social satire, with the narrator questing after a true Christian life.

Conquest of Herat in Afghanistan by Timur (also known as Tamerlane or Timur the Lane). The conqueror from central Asia embarked on over 20 years of continuous warfare leading to the creation of theTimurid dynasty and Timurid Empire.

English author Geoffrey Chaucer begins work on his magnum opus, The Canterbury Tales. Pilgrims travelling between London and Canterbury take part in a story telling contest on their journey to the shrine of Saint Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral.

-min.jpeg)

-min.jpeg)

-min.jpeg)

-min.jpeg)