The peak of the Black Death in Europe occurred in the middle of the 14th century, from roughly 1348 to 1351. The devastation it caused, in terms of the lives lost and the impact on societies across the continent was profound. However, the disease would return intermittently over the decades that followed, with deadly outbreaks ravaging different communities to cause more sorrow and loss. Because of this, the aftermath of the plague was characterised by a combination of both short- and long-term consequences.

The plague effectively changed Medieval Europe in a number of profound ways. The devastation and death it had been responsible for made it very difficult for people from all strata of society to return to the lives they had previously known. For some, this offered opportunities to carve out new and better conditions for themselves and others. For others, the plague posed profound threats to life as they knew it. For other still, the plague changed their very understanding of the world around them.

From old certainties, broken and buried by the devastation of the Black Death, came new visions of the world.

Prior to the plague, Europe’s peasants lived under the authority of rigid, hierarchical systems. Social mobility was almost non-existent, and the horizons of a peasant may well have been no broader than his immediate community. Peasants and serfs effectively found themselves at the lowest rung of a hierarchy, at the top of which were kings and nobility. Existing in several forms, this may broadly be classified as the feudal system.

Under feudalism, a noble might hold lands from the Crown, in exchange for providing military support (the nobles served as the King’s knights, for instance). In turn, a number of peasants or serfs worked this land. They were obliged to pay homage to the nobleman on whose land they lived, as well as providing labour (as farmers, for example), and a share of the produce they cultivated (crops etc). The hierarchical nature of the structure, with land concentrated in the hands of the noble minority, reduced almost all opportunities for upwards social mobility.

This changed with the massive depopulation resulting from the plague, which naturally killed indiscriminately; a man’s nobility could not protect him from yersinia pestis, after all. Suddenly, serfs and peasants found themselves in demand: who else was going to work the land and continue to produce the crops? Suddenly, they held a much stronger negotiating position, to seek better wages and conditions. For example, in 1348, the Early of Stafford in England was paying his farm labourers one pence a day. By 1350, they were obliged to increase it to two pence a day; some landowners were even paying three pence a day!

The response of the aristocracy after the worst of the plague had passed was to attempt to reimpose the previous hierarchies in anyway possible. This happened across Europe in a variety of different ways. Sumptuary laws were passed across the continent, and these aimed at limiting what peasants could wear to help distinguish them from nobles, in quite literally a case of ‘keeping up appearances’. The improved wages of the lower classes had allowed them to begin to enjoy the finer things in life. In 1351, the Statute of Labourers was passed in England. This meant that no peasant was able to ask for more wages than they had been receiving in 1346.

“That every man and woman of our kingdom of England... who is able bodied and below the age of sixty years, not living by trade nor carrying on a fixed craft, nor having of his own the means of living, or land of his own... shall be bound to... take only the wages... (that) were paid in the twentieth year of our reign of England (i.e. 1346) ...” Extract from the Statute of Labourers, 1349

In England and France, the situation became violent quite rapidly. There had already been peasant riots in France in 1358, and a series of guild revolts in 1378, but the most shocking event was the Peasants’ Revolt in England in 1381. An attempt to collect unpaid poll taxes for the crown was the catalyst for a widespread, violent revolt. The uprising peasants wanted, among other things, a reduction in taxes. Led by Wat Tyler the peasants marched on London, destroying parts of the city including the Savoy Palace. The revolt was quelled only when King Richard II’s soldiers killed Wat, although it took some time to quell all of the violence across the country. By November, some 1,500 rebel peasants had been killed.

Ultimately, the Black Death laid bare the limitations of medieval medicine. Millions of people perished because of a lack of understanding of what caused disease and how to counter their spread. However, the devastation caused by the disease did contribute to significant changes in medicine that would be important in the centuries that followed.

On the one hand, much as it had with Religion and people’s faith, the Black Death prompted people across Europe to challenge established medical knowledge. Doctors – like priests and noblemen – were just as likely to die as a result of the disease, undermining their alleged expertise. To make matters worse, their treatments were of varying quality; a cure that saved one patient may have had no effect on another…

Most people in Europe would still have relied on herbal and traditional remedies to attempt to treat diseases and other maladies. This can be linked to established beliefs, such as in the ability of miasmas (‘bad air’) to spread diseases. Likewise, the theories from the ancient world – the ideas of Hippocrates and Galen, including the theory of Four Humours – also remained important. The attempts to work with this theory involved rudimentary practices, such as bleeding. Elsewhere, surgery remained dangerous, dirty, and excruciatingly painful.

Despite this, there were some important changes in medicine during and as a result of the Black Death. Figures such as Guy de Chauliac began to examine and record anatomy in greater detail, and the importance of observation as a medical principle became clearer. The plague also prompted some governments – on a local level at least – to begin to introduce legislation and changes that aimed at ensuring outbreaks could not recur. Although these relied on misplaced belief in the efficacy of theories such as miasma, they demonstrate a positive step toward improving public health.

The 14th century was an important era for cultural developments. Figures such as Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio helped usher in new literary cultures and shaped not only the way people understood the world around them and their place in it, but also how they communicated these ideas with each other. In the decades that followed the height of the Black Death in the mid-14th century, the effect of the plague on European culture become ever clearer, characterised by a hardly unsurprising macabre character…

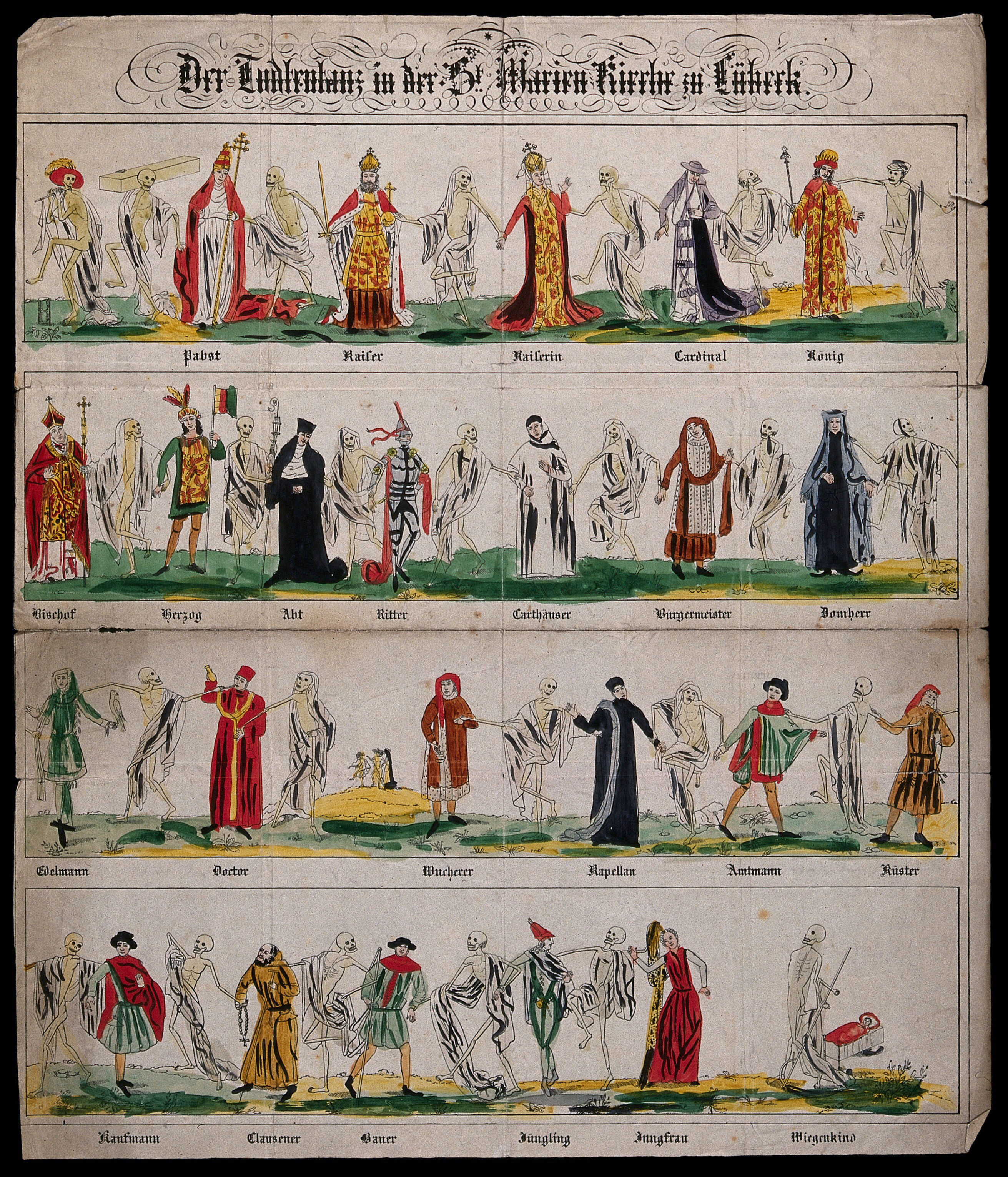

The influence of the plague can be seen in the increased realism in medieval art after the plague. The devastation it had caused stripped away any semblance of idealism. A recurrent subject in medieval art after the mid-14th century was the Danse Macabre (‘The Dance of Death’), which used allegory – rather than an explicit depiction of death – to show how Death came for all; this was a cultural motif that manifested the devastation of the plague. The increased emphasis on realism in art, which was evident already in some artworks, most famously in Giotto’s works. This approach to representation would continue to spread around Europe in the centuries that follow. Europe was about to usher in the Renaissance, as cultural ideas from the societies of ancient Greece and Rome came to the fore once more in culture.